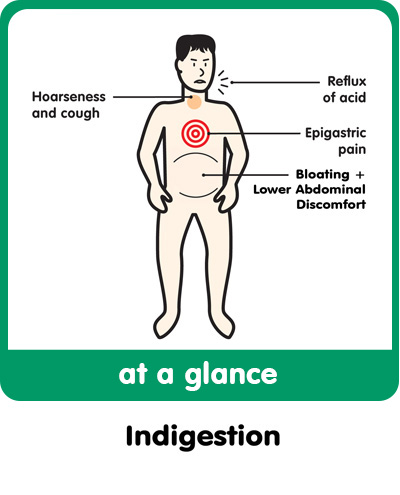

Indigestion

Indigestion encompasses a vast array of symptoms in the upper digestive tract, including:

· Heartburn

· Fullness

· Early satiety

· Upper abdominal ache or pain

· Flatulence

· Hiccoughs

· Belching

These symptoms are known collectively as dyspepsia, and this occurs in up to 10% of the adult population. At least half of these seek medical help, and dyspepsia accounts for 40% of referrals to a gastroenterologist.

Dyspepsia can be classified in three ways:

· ‘Reflux-like’ if heartburn or chest pain predominate

· ‘Ulcer-like’ if it gives the impression of a peptic ulcer

· ‘Functional’ if there is no clear sign of organic disease

Reflux-like Dyspepsia:

Heartburn is the key to identifying reflux-like dyspepsia. It is described as a burning sensation felt behind the sternum or breastbone. It is a diffuse pain and is usually made worse by lying down or leaning forward. ‘Waterbrash’ is excessive saliva production as a response to the presence of acid in the lower oesophagus.

Pain due to heartburn often radiates between the shoulder blades, whereas oesophageal spasm (sometimes triggered by acid reflux) more commonly causes chest pain, and can be mistaken for cardiac chest pain. Oesophageal spasm pain is typically

· Felt behind the sternum

· Often severe

· Feels like a squeezing inside

It can be differentiated from cardiac chest pain by the facts that

· Oesophageal pain is not provoked by exertion

· Oesophageal pain can be made worse by lying down or leaning forward

Some patients with severe acid reflux do not complain of pain, but instead a cough or wheeze at night when they are lying flat.

Risk factors for reflux include:

· Increased intra-abdominal pressure

· Stooping and bending

· Spicy foods

· Alcohol

· Cigarettes

· Caffeine

· Neuroleptic drugs

Standard medical treatment includes lifestyle changes:

· Smaller meals

· Stopping smoking

· Reducing alcohol intake

· Losing weight

· Not eating late at night

· Raising the head of the bed

· Not drinking with meals

In addition simple antacids, or medications such as ranitidine or omeprazole which irreversibly blocks acid production, are employed.

The second classification of Dyspepsia is Ulcer-like Dyspepsia:

Ulcers occur when the surface epithelium of the stomach or duodenum is damaged, and the resulting inflammation into the underlying mucosa and submucosa. Gastric acid and digestive enzymes penetrate into the tissues, causing further damage. Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that is implicated in the majority of patients with peptic ulcers. Eradicating H.pylori infection permanently cures peptic ulcers in the majority of cases. Peptic ulcers may cause acute bleeding and blood in the stools. If blood is found in the stools, you should see your doctor immediately.

In patients with ulcer-like dyspepsia, the history of the complaint is often vague, and the pain is more akin to a gnawing sensation, or a dull ache. Patients can often point to a specific location for the sensation, and a gastric or stomach ulcer is often worse immediately after eating.

Duodenal (the part of the digestive tract immediately after the stomach) ulcer pain is commonly relieved by antacids, and is often worse at night, and without eating.

Usual medical treatment regime is a combination of an acid suppressor and two or three antibiotics. Most standard regimes are successful in 90% of cases, although reoccurrence rates are as high as 80% after twelve months.

Risk factors for peptic ulcer disease include:

· Family history of peptic ulcer disease

· Smoking and alcohol consumption

· Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use (NSAID), including aspirin, which inhibit prostaglandin production.

The third classification, Functional Dyspepsia is used when dyspepsia symptoms occur in the absence of demonstrable acid reflux or Helicobacter pylori related disease (gastritis; duodenitis; and gastric or duodenal ulcers).

Showing all 2 results

-

Custom Probiotics Yoghurt starter probiotic powder Culture One 25g

£55.00 Add to cart -

Custom Probiotics Yoghurt Starter probiotic powder Culture Two 25g

£55.00 Add to cart

Showing all 2 results