Peptic Ulcer

What is a peptic ulcer?

What is a peptic ulcer?

A peptic ulcer is a hole in the gut lining of the stomach, duodenum, or esophagus. A peptic ulcer of the stomach is called a gastric ulcer; of the duodenum, a duodenal ulcer; and of the esophagus, an esophageal ulcer. An ulcer occurs when the lining of these organs is corroded by the acidic digestive juices which are secreted by the stomach cells.

What are the causes of peptic ulcers?

For many years, excess acid was believed to be the major cause of ulcer disease. Accordingly, treatment emphasis was on neutralizing and inhibiting the secretion of stomach acid. While acid is still considered significant in ulcer formation, the leading cause of ulcer disease is currently believed to be infection of the stomach by a bacterium called Helicobacter pylor (H. pylori). Another major cause of ulcers is the chronic use of non steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, (commonly referred to as NSAIDs), including aspirin. These inhibit prostaglandin production by epithelial cells. NSAIDs are medications for arthritis and other painful inflammatory conditions in the body. Aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin), naproxen (Naprosyn), and etodolac (Lodine) are a few of the examples of this class of medications. Prostaglandins are substances which are important in helping the gut linings resist corrosive acid damage.

Aggressive factors like cigarette smoking and alcohol can also play an important cause of ulcer formation and ulcer treatment failure.

The H. pylori bacterium is very common, and it is estimated that around 80% of us are carriers, with infection usually persisting for many years, leading to ulcer disease in only 10 % to 15% of those infected. H. pylori is found in more than 80% of patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers. While the mechanism of how H. pylori causes ulcers is not well understood, elimination of this bacterium by antibiotics has clearly been shown to heal ulcers and prevent ulcer recurrence in the majority of cases.

Strains of H. pylori vary in pathogenicity and virulence, and so both host factors and the bacterial strain determine the outcome of infection.

Contrary to popular belief, alcohol, coffee, colas, spicy foods, and caffeine have no proven role in ulcer formation. Similarly, there is no conclusive evidence to suggest that life stresses or personality types contribute to ulcer disease.

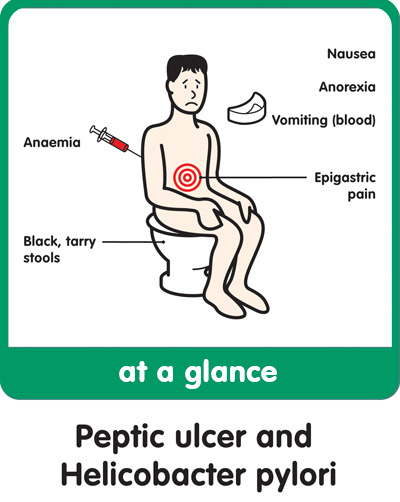

What are symptoms of an ulcer?

Symptoms of ulcer disease are variable. Many ulcer patients experience minimal indigestion or no discomfort at all. Some report upper abdominal burning or hunger pain one to three hours after meals and in the middle of the night. These pain symptoms are often promptly relieved by food or antacids. The pain of ulcer disease correlates poorly with the presence or severity of active ulceration. Some patients have persistent pain even after an ulcer is completely healed by medication. Others experience no pain at all, even though ulcers return. Ulcers often come and go spontaneously without the individual ever knowing, unless a serious complication (like bleeding or perforation) occurs.

How is an ulcer diagnosed?

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the best diagnostic test, but ulcers can also be detected by barium contrast X-rays. They can also be detected by the urease breath test in which C-labelled urea is taken orally and the resultant C02 released by the urease enzyme is measured on the breath.

What are ulcer complications?

Patients with ulcers generally function quite comfortably. Some ulcers probably heal even without medications. Therefore, the major problems resulting from ulcers are related to ulcer complications, including ulcer bleeding, ulcer perforation, and gastric obstruction.

Patients with ulcer bleeding may report black tarry stools (melena), weakness, a sense of passing out upon standing (orthostatic syncope), and vomiting blood (hematemesis). Initial treatment involves rapid replacement of lost body fluids intravenously. Patients with persistent or severe bleeding may require blood transfusions. An upper endoscopy is performed to establish the site of bleeding and to stop active ulcer bleeding with the aid of heated instruments.

Ulcer perforation leads to the leakage of gastric contents into the abdominal (peritoneal) cavity, resulting in acute peritonitis (infection of the abdominal cavity). These patients report a sudden onset of extreme abdominal pain, which is worsened by any type of motion. Abdominal muscles become rigid and board-like. Urgent surgery is usually required.

Patients with gastric obstruction often report increasing abdominal pain, vomiting of undigested or partially digested food, diminished appetite, and weight loss. The obstruction usually occurs at or near the pyloric canal. The pyloric canal is a naturally narrow part of the stomach joining the upper part of the small intestine called the duodenum.

Upper endoscopy is useful in establishing the diagnosis and excluding gastric cancer as the cause of the obstruction. In some patients, gastric obstruction can be relieved with tube suction of the stomach contents for 72 hours, along with intravenous anti-ulcer medications, such as cimetidine (Tagamet) and ranitidine (Zantac). Patients with persistent obstruction require surgery.

Why treat H. pylori?

Chronic infection with H. pylori weakens the natural defenses of the lining of the stomach against the ulcerating action of acid. Medications that neutralize stomach acid (antacids), and medications that decrease the secretion of acid in the stomach (H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors or PPIs) have been used effectively for many years to treat ulcers. H2-blockers, include ranitidine (Zantac), famotidine (Pepcid), cimetidine (Tagamet), and nizatidine (Axid).

PPIs include omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (Aciphex), pantoprazole (Protonix), and esomeprazole (Nexium). Antacids, H2-blockers and PPIs, however, do not eradicate H. pylori from the stomach, and ulcers frequently return promptly after these medications are discontinued. Hence, antacids, H2-blockers or PPIs have to be taken daily for many years to prevent the return of the ulcers and the complications of ulcers such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction of the stomach. Eradication of H. pylori prevents the return of ulcers and ulcer complications even after the medications are stopped. Eradication of H. pylori is also important in the treatment of the rare condition known as MALT lymphoma of the stomach.

Pharmaceutical anti-ulcer drugs reduce the acid in the stomach, allowing a temporary healing, but they also can also cause a number of negative side effects. They deprive the body of acid, which is necessary for digestion, for protection against unfriendly bugs, for good bone health, and for turning on the rest of your digestive enzymes. These drugs may block good prostaglandin production, which can cause inflammation and cellular damage in your body. They can damage your gastrointestinal lining. Many of these anti-ulcer medications (H2-receptor blockers) allow the growth of all kinds of viruses, bacteria, and fungi such as candida albicans, which would normally have been killed in the stomach. There is also a high rate of relapse with pharmaceuticals, 80% after one year and 100% after two years.

Showing the single result

Showing the single result